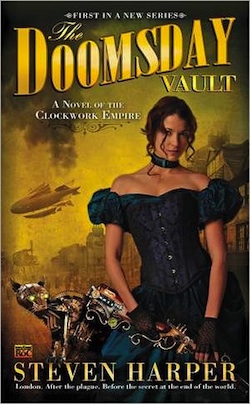

An Introduction to Steven Harper’s The Doomsday Vault

By Penguin (Ace/Roc) SFF editor Anne Sowards

At its core, steampunk is fun. Where else can you find fantastical gears and gadgets, airships, clockwork cats, mad geniuses, walking mechanical trees, zombies, and pirates, all wrapped up in pseudo-Victorian mores, manners, and fashion? And those are just some of the awesome things you’ll encounter in Steven Harper’s first novel of the Clockwork Empire.

But what first got my attention when I started reading The Doomsday Vault is The Dress. That’s right, The Dress. One of the things I love about steampunk is its juxtaposition of the very proper 19th century sensibility with Go-Go-Gadget wackiness. In the opening chapter, the Honorable Alice B. Michaels is making her way to the event of the season, a party her father has called in all his favors to get her in to. You see, due to the death of most of her family from the clockwork plague, she’s a social pariah, and this is her last-ditch effort to snag a husband. As part of this, she’s wearing The Dress, which is such an impressive fashion creation that it’s worthy of a proper noun. Over the course of the evening, Alice finds herself under attack by plague zombies—and the fate of The Dress? Well, you’ll have to read the book to find out.

Chapter One

The zombie lurched out of the yellow fog and reached for the door on Alice’s hansom cab. Alice Michaels shied away.

“Driver!” she shouted.

“I see it, miss.” The driver leaned down from his seat above and behind Alice and cracked the zombie smartly across the forearms with his carriage whip. The zombie groaned. Its face was a mass of open sores, and its skin had worn through in places, exposing red muscle beneath. Old rags barely covered its body. Fear and adrenaline thrilled through Alice’s veins as the zombie’s festering arm reached through the open sides of the cab. She pushed herself away from it, but there wasn’t much room in the little two-wheeled cab, and The Dress hindered her movements. The driver lashed down with the whip again. The zombie abruptly let the cab go, and the driver smacked the reins across the horse’s rump. Alice clutched a handle inside the cab as it bounced across the cobblestones, the wheels pounding as hard as her heart. Despite herself, she turned on the leather-covered seat and looked out the rear window. The zombie was already fading into the night and mist.

A particularly rough bounce jolted Alice to her teeth. “You can slow down now,” she called. “It’s gone.”

The driver obeyed, and Alice resettled The Dress about her. The Dress was a deep violet affair with multiple flounces, fashionably puffed sleeves, and a short matching shawl to ward off the damp spring chill. The layers formed a heavy shell around her, concealing her pounding heart and shaking knees beneath a veneer of smooth satin. It had cost Father an enormous sum, and Alice realized she had been more afraid of the zombie’s tearing The Dress than of the creature’s touching and infecting her.

“You all right, miss?” the driver called down from his seat.

“I’m fine. Thank you for fending it off.”

The driver touched the brim of his high hat, and Alice realized she was required to tip him extra. She made a mental inventory of the coins in her purse and decided she could do it, but only if the driver on the return trip would be willing to wait while she ran into the house for tuppence. It would make her look foolish, but there was nothing for it.

Yellow gaslights lit the London evening as the horse clopped through winding streets, the driver keeping carefully to the better-traveled avenues. Other carriages and cabs pulled by horses both living and mechanical joined them. Overhead, Alice heard the faint whup-whup-whup noise of a dirigible’s propellers, and its massive, blunt shape made a black spot among the misty stars. Restaurants and pubs kept their doors open and their windows lit—lights kept the zombies at bay. Smells of coal smoke, manure, and wet wool permeated the air. People strolled in couples or groups on the sidewalks, heading to or from concerts, plays, parties, celebrations, and other social events. It was a Saturday evening in May, and the London spring season was in full swing. Alice watched the men in their dark trousers and coats, and the women in their skirts that belled and swayed with every step, and she wondered what flaws each one was hiding beneath sartorial perfection.

Mere clothing wouldn’t hide Alice’s shortcomings. A new dress couldn’t smooth over the fact that she was still unmarried at the age of twenty-two, or that twelve years ago, her mother and brother had died in the same outbreak of clockwork plague that had left her father a cripple, or that three years ago, Alice had become engaged to Frederick, heir to the Earl of Trent, only to watch the clockwork plague kill him as well. After that, no one wanted anything much to do with the Michaels family. Their fortunes, both monetary and social, had declined sharply. Alice would gladly have found some kind of useful work, but traditional society had long ago decreed that the daughter of a baron was expected to be a lady of leisure, no matter how badly her family might need money, and her family’s history with the clockwork plague precluded her from trying to find a position as a lady-in-waiting. This dance was her last chance to redeem the Michaels’ social graces.

The cab drew up to a large three-story town house with a cobblestoned courtyard and fountain out front. Electric lights, the new fashion, blazed in all the windows, and a short line of cabs and carriages snaked around the courtyard. Alice checked the pocket watch inside her purse. Nine fifteen. She had arrived late, but not fashionably late—all part of her strategy. The majority of the guests would arrive after ten, and Alice hoped her arrival to a nearly empty ballroom would allow her lack of an escort to go unnoticed, or at least unremarked. Alice’s mother would have been her first choice as escort, of course, and her brother second, but neither of them was available.

While they were waiting in line, Alice paid—and generously tipped—the driver so she wouldn’t have to do so in front of her hosts. The daughter of a traditional baron didn’t handle financial transactions, but Alice didn’t have much choice, sitting in the shabby cab she had hired herself. She couldn’t help but notice that many of the other conveyances were richly appointed, private carriages or, at a minimum, hired cabs of a better class than hers. A few were pulled by steam-snorting mechanical horses. The couple directly behind Alice arrived in a rickshaw pulled by a brass automaton shaped roughly like a man. Alice stared thoughtfully at it, trying to trace how the gears underneath its smooth metal skin would be put together, where the pistons would be placed, how the boiler would deliver proper power. It would be so much more interesting to spend the evening pulling the automaton apart and putting it back together than—

The woman in the rickshaw glanced at Alice’s little hired hansom, cracked open her fan, and whispered something behind it to her male companion. They both laughed. Alice’s cheeks burned, and she sat rigidly upright in her seat, determined to brazen this out. Father had used up his final favors among certain business contacts to get Alice this invitation, and she wasn’t going to fail him.

At last, Alice’s cab came to the front door. A footman in gold livery helped her down, but she had to walk through the double doors into the house by herself. Light music—all sweet strings in a major key—drifted from the house’s interior. Inside was a large, marble-floored foyer, where a starched servant girl took Alice’s shawl and pointed her toward the main ballroom. Alice, back straight, pleasant smile on her lips, swayed toward the door, where Lady Greenfellow, the hostess, had stationed herself to greet her guests. She was a heavyset woman whose wrinkled face belied her jet-black hair, and her dark green dress wrapped her high and low. Alice extended a gloved hand.

“Thank you so much for inviting me, Lady Greenfellow,” she said earnestly.

“Of course,” Lady Greenfellow replied. “My husband was quite insistent that you should come, on account of your father. And how is dear Arthur these days?”

“He’s well,” Alice said.

“Wonderful to hear.” The warmth in Lady Greenfellow’s tone was as false as her hair color. “How time flies. I still remember that day I found you on the street with those adorable urchins. How long ago was that?”

For a terrible moment, Alice’s hand moved to slap Lady Greenfellow’s wrinkly cheek. Instead, she opened her fan and waved it idly. “My impetuous days are long behind me.”

“Of course. And you do look lovely tonight.”

Alice hoped that was true. Her honey brown hair was pinned up in the latest style, leaving a single stream of curls trailing down the left side of her face, and her cosmetics were artful enough that no one could tell she was wearing any at all. She had a triangular chin and pert nose, and The Dress hid the fact that her legs and body had grown rather thin in recent months. Her shoes had no heel to conceal her height. “Thank you,” she said.

“But, my dear”—Lady Greenfellow peered over Alice’s shoulder at the foyer behind her—”you didn’t even bring a maid! You’re not here on your own, are you? I didn’t think Arthur would allow his daughter to become one of those new Ad Hoc women.”

“Not at all. Bridget tripped and sprained her ankle just as we were leaving,” Alice said, giving her prepared lie. A trickle of sweat ran down her back. “It was too late to engage another maid, so here I am.”

Lady Greenfellow clicked her tongue. “Misfortune does follow you. Well, the ballroom is through there, and sitting rooms are that way. Our supper buffet begins at one.”

Approved and dismissed, Alice nodded with relief and stepped into the main ballroom. The main hurdle was over.

The ballroom was a two-storied affair, with a balcony that ran around the upper half. Lush arrangements of fresh red and white roses covered the balcony rail and hung nearly to the floor below, filling the air with the sweet smells of nectar. The string players were stationed upstairs, their rubber-tipped fingers weaving a soft, melodic tapestry at odds with their hard metal faces. High windows looked out on the city, and an enormous electric chandelier—the showpiece of the house—provided bright light. Refreshment tables and sitting areas ringed the polished oak dance floor. Barely twenty people wandered among them, every one much older than Alice, who at twenty-two,was fast becoming an old maid. She handed one of her name cards to the elderly butler stationed at the door.

“The Honorable Alice B. Michaels,” he announced over the music.

Reflexively, everyone in the room turned, nodded at Alice, and went back to their conversations. Alice allowed herself a moment of relief—her unescorted entry hadn’t caused even a ripple. Expression pleasant, she drifted toward a refreshment table and found herself falling back into a rhythm she hadn’t felt since Frederick’s death had cast her from the social rolls: pluck a dance card from the tray at the table, tie the ribbon to her fan so she could flash it at eligible gentlemen or conceal it from less desirable ones, select a glass of champagne from the arrangement, let her gaze wander about the room to see who else had arrived. So far she didn’t recognize anyone, which made things awkward—women could converse only with other women, and only a man could ask for a dance. She made herself pointedly available for approach, either for a dance or for conversation.

No one came near her. After a bit, she went up to the balcony to look at the orchestra. A dozen faceless automatons played violin, viola, cello, drum, and other instruments. No music stands or music stood before them, and no conductor waved a baton. Their brass skins gleamed in the light of the chandelier, and Alice was surprised at the sweet precision of the music they produced. Their movements, however, jarred. The fingers moved with quick grace, but the torsos remained motionless, in stark contrast to human musicians, who played with their entire bodies. This orchestra were really nothing more than a giant music box, and Alice decided she’d much rather let a set of live musicians sweep her away.

The cello player faltered. Its bow squawked across the strings, and the dissonance tore through the delicate music. The other musicians continued to play as if nothing had happened. On the floor below, several dancers winced and faltered in their steps. Without thinking, Alice reached in and plucked the bow from the cello player’s fingers. The cello went silent, and the waltz continued with a missing instrument. The cello player jerked in its seat, fingers twitching spasmodically over the strings.

“What’s going on up here?” demanded Lady Greenfellow, skirts still swirling from her indignant scurry up the staircase. “What on earth are you doing to my musicians?”

Alice suppressed a desire to hide the bow behind her back. “I think something went wrong with your cello player,” she said, ignoring the accusation. “I took the bow away before the noise could ruin the dance. Do you have an automatist on staff?”

“No.” Lady Greenfellow’s face flushed. “And we’ll never find one at this time of night. Now what do I do?”

Alice hesitated, then plunged ahead. “I could have a quick look,” she offered. And before Lady Greenfellow could object, Alice scooted around behind the players, stripped off her gloves, and leaned in to pop the rear panel off the errant cellist. The musicians played mechanically on as Alice peered inside one of their number. Gears whirled, oil dripped, and the wheels of an analytical engine spun merrily, trying to direct a body that refused to obey properly. A fascinating little world, where everything was connected to everything else. Alice found herself drawn in, searching for the patterns and for the flaw causing the problem. Her heart quickened a little, and she had to admit she was showing off a bit for her hostess. It wasn’t correct ballroom behavior for a traditional lady, but Alice had been shunned so far. What did she have to lose?

“I don’t think this is quite—” Lady Greenfellow began.

“There’s your problem,” Alice said. “One of the drive pistons has become disconnected, and it’s throwing off the machinery. Easy enough to fix.” Without thinking, she drew back her sleeve to midforearm and reached inside. Lady Greenfellow huffily turned her back and spread herself as wide as she could to provide cover. Alice reconnected the piston and snatched her hand free as it started up again. She put the panel back on, delicately wiped machine oil from her fingers with a handkerchief, and handed the bow back to the cellist, who rejoined the song in progress.

“All fixed,” Alice said, donning her gloves.

Lady Greenfellow turned around and stared. “I . . . see. Thank you.” Her words were stiff, more ice than gratitude.

“Not at all,” Alice replied, feeling her heart sink. Clearly, having a woman—or perhaps this particular woman—rescue the mechanical musicians wasn’t going to provide the social coup Alice had been hoping for. Perhaps this would be a good time for her first swear words.

Alice went back downstairs as more guests arrived. She began to recognize people—girls she had gone to school with, attended dances with, discussed weddings and social outings with. They were all married now, attending the dance with their new husbands. And they all ignored Alice. When she approached, they glided away. When she stood still, they kept their distance. None of the men asked Alice for a slot on her dance card. Couples young and old whirled and glided across the dance floor. At first, Alice felt self-conscious and embarrassed, sitting at a small table by herself. Then she felt angry. Then she felt desperate. This was supposed to be her reentry into society, and—

“Not going well, is it?” A woman in a startlingly low-cut blue gown plunked down in a chair opposite Alice’s at the table. “What a bunch of bores.”

“I’m sorry,” Alice said, “I’m afraid I—”

“Louisa Creek,” she said, extending a hand. She looked quite a few years older than Alice. Artful cosmetics couldn’t conceal a bad complexion or a beaky nose, though her thick black hair was coiled in a complex braided bun. Alice tried to guess at her age, but she could have been anywhere from her early thirties to her late forties. The dance card hanging from her fan was as empty as Alice’s. “You’re Lady Alice—or you will be, once your father dies. We’ve never met, but I’ve heard of you. Terrible situation. The clockwork plague hits your family twice, and everyone treats the survivors like lepers. An apt simile, I suppose.”

“I suppose,” Alice said. She found Louisa’s forthrightness shocking, but also a little thrilling. Daring. “Aren’t you afraid everyone will see you talking to me and begin to treat you the same way?”

“It doesn’t matter who I talk to.” Louisa cracked her fan open and waved it nonchalantly. “See that . . . gentleman over there in the badly cut jacket? Ash-blond, a little short, talking to the bald fat man?”

“Yes.”

“He’ll eventually ask me to dance. And so will that man over there, the one hovering near the ice sculpture.”

“How do you know they’ll ask you?”

Louisa grinned. “They’re second sons, dear. No inheritance prospects. But I have pots of money, which makes me an enormous prospect, even if I’m that much older than they are. That’s why I can have a less-than-beautiful face and talk to lepers.” She smiled and patted Alice’s hand to show it was a joke. “Are you an Ad Hoc lady?”

“Good Lord, no. Are you?”

Louisa waved her fan. “I haven’t decided. Wouldn’t it just shock these stuffies? It’s been legal for us to vote for three years now, thanks to the wonderful work of the Hats-On Committee in Parliament, but if we take advantage of it, certain people act as if a cow wanted to recite Shakespeare.”

Alice gave a weak smile in acknowledgment. Three years ago, the same wave of clockwork plague that had killed her fiancé, Frederick, had also incapacitated several prominent members of Parliament, threatening to cripple the entire government. In a surprise move, their wives took over their affairs, writing letters, giving speeches, and even voting in their husbands’ names while the emergency lasted. They created the Hats-On Committee, so nicknamed because the members didn’t remove their hats indoors. Rumors abounded of an anonymous benefactor who provided the committee with money and other resources, though nothing was ever proven. By the time their husbands died from the plague, this “ad HOC” group had gained enough power and support to push through one important piece of legislation: suffrage for women. Females could now vote and hold office, just like men. Legal sanction, however, didn’t always grant social acceptance, especially among the upper classes.

“My father would have a fit if an Ad Hoc lady turned up in the family,” Alice said. “I wouldn’t do that to him. It would certainly ruin my chances here.”

“How did you get invited in the first place?” Louisa asked.

“Father called in a final favor.” Alice set her mouth, not sure whether she was going to laugh or cry. “This was to be a step forward for us. I would comport myself well, attract the eye of the gentlemen, and Father’s business contacts would start turning up again.”

“Good plan,” Louisa said. “A damned pity it’s not working. Word has it you came unescorted in a cab.”

“My maid twisted her ankle—”

Louisa waved this aside with her fan. “It’s a good lie, but it fades when you repeat it. Be brazen! No one likes a beggar, even an invited beggar, so don’t act like one.”

“But I need them,” Alice said, gesturing toward the couples on the floor.

“Less than you think. You’re pretty and you’re smart, and that’s a deadly combination. Nice job repairing Lady Greenfellow’s cellist, by the way. Very Ad Hoc. If it had been anyone but you, the old bat would have been grateful. Oh look—here comes my first.”

The ash-blond man in the badly cut coat Louisa had pointed out earlier came around the dance floor to the table. “May I have the honor of a dance?”

“Let me check my card,” Louisa said, doing so. “I seem to be free. Shall we?” She gave Alice a final wink as her new escort led her away while the women who weren’t dancing murmured to one another behind their fans. Chagrined, Alice watched Louisa go. Perhaps it was time to slip away and go home. There was nothing for her to—

“May I have the honor of a dance?”

The man was older than Alice, nearly thirty, tall and lean, in a stylish Fairmont waistcoat and shining black silk coat. His brown hair and muttonchop whiskers were neatly trimmed, and his dark brown eyes looked pleasantly down at her. His features were attractive though not quite handsome.

Alice was so startled, she forgot she was supposed to check her dance card. “I would be delighted, sir,” she said, taking his hand and rising. “But I don’t know your name.”

“Mr. Norbert Williamson, at your service,” he said instantly. “And you, I believe, are Miss Alice Michaels. I’ve done some work with your father, Lord Michaels.”

The orchestra ended the waltz and swept into a gavotte, precise and perfect as an ice sculpture. Norbert guided Alice to the dance floor and put his hand on her waist. Several couples gave them sideways looks, but most ignored them.

“Everyone is talking about how you repaired the cellist,” he said as they moved across the polished wood. “Your father says you have quite a talent with automatons, Miss Michaels.”

“That’s kind of him,” Alice replied, surprised. “I suppose it’s because I find automatons more interesting than people.”

“Oh.”

An awkward silence followed, and Alice mentally kicked herself. “But not tonight,” she added hastily. “I haven’t been out in so long, I’d forgotten how enjoyable it is. Dancing is so much fun, especially with a talented partner like you, Mr. Williamson.”

She couldn’t quite bring herself to bat her eyes, but the flattery had its intended effect. His arms relaxed a little, and he smiled.

“What do you think of the orchestra?” he asked. “Now that it’s working.”

“They play very nicely,” she said, and let herself sway a little more with the rhythm. “I love music of all sorts, but I have no talent at making it. Do you play an instrument?”

“I’m completely tone-deaf,” he said, and Alice was surprised at how deeply the admission disappointed her. “Lady Greenleaf’s players need to be serviced more often,” he continued, oblivious. “The cellist wouldn’t have seized up like that if I were in charge of it.”

“Are you an automatist by trade, Mr. Williamson?”

He shook his head. “My company makes machine parts. Automatons are a bit of a hobby. I think that’s why your father is trying to fling us together.”

Alice’s heart quickened despite her earlier disappointment. This was the main reason she was here, then. Norbert Williamson was a marriage prospect. He swung her around, and Alice smiled up at him. Her job was to be winning and witty.

“He shouldn’t need to fling anything, Mr. Williamson,” she said. “If you enjoy automatons, we have a lot in common. What are your views on the idea that Charles Babbage took credit for Ada Lovelace’s work with the analytical engine?”

“I do enjoy automatons,” Norbert said. “But for the moment, I’d prefer to dance with a beautiful woman.”

It was empty flattery, but it was nice to hear. They danced three dances before Alice pleaded the need to rest; Norbert immediately guided her back to the side tables and went off in search of refreshments. The moment he was gone, Louisa all but hurled herself into a neighboring chair.

“Norbert Williamson?” Louisa said. “How interesting.”

“What do you know about him?” Alice demanded. “Quick!”

“Very little. He’s new to London. No title, so he’s not a peer. He bought a factory, and it’s making good money. He seems to have a lot of male friends, and for a while rumors were circulating that he runs with the bulls, if you know what I mean.”

“Louisa!”

“Oh, as if you’ve never come across the type.” Louisa laughed. “But lately he’s been showing himself at a lot of social events and sniffing around some heifers. He’s a traditional man, not Ad Hoc, and probably interested in your title.”

“He wouldn’t get it,” Alice said. “It’ll come to me, and then only because Father has no male relatives. After that, it’ll go to my first son, never my husband.”

“Close enough for us mere commoners,” Louisa replied. “Puff up your chest, dear. Here he comes with the petits fours.”

Two more dances followed, and Norbert accompanied Alice to the buffet supper at one o’clock. Alice was starving, but she restricted herself to proper ladylike servings of veal escalopes, carrots Vichy, and gooseberry fool. Norbert, for his part, remained attentive and charming. Alice liked his company well enough, though she didn’t feel any of the pounding, heaving, or poetic emotions referred to in any of the poetry or . . . less literary work about romance she had read over the years. Norbert certainly seemed interested in her, and Alice did find that both heartening and satisfying. It was nice to know someone found her desirable.

They were just moving back to the dance floor when a delicate brass dove fluttered into the ballroom and landed on Norbert’s shoulder. With a surprised look, he opened a small panel on the back, removed a slip of paper, and read. Alice took the bird from him and examined it. The delicate work on the feathers was particularly fine. The glassy eyes were bright and alert, and it moved realistically in her gloved hands.

“I’m sorry, Miss Michaels, but a situation has arisen at my factory and I must leave,” Norbert said. “And here I was hoping to see you home. Do forgive me.”

And then he was gone, the dove fluttering after him.

“Everyone’s talking about you,” Louisa said, appearing at her elbow like magic.

“Is that good or bad?”

“Hard to tell. Norbert Williamson is the joker in the pack. No one knows what he’s really about, so they don’t know how to react to him—or to you, now. But they’re still not talking to you. The men are afraid of the clockwork plague, and the women are afraid that anyone who talks to you won’t be asked to dance by anyone good.”

Alice sighed, suddenly tired. “Except you.”

“There are advantages to having one’s own money,” Louisa said without a shred of self-consciousness. “Patrick Barton—the ash-blond one in the bad coat—is seeing me home tonight. And he’ll probably have breakfast.”

It took a moment for the meaning to sink in. Alice snapped open her fan, scandalized. “Louisa!”

Louisa laughed again. “You need to have more fun, Alice. Call on me, darling. I should mingle.” And she left.

Exhaustion settled over Alice, and the ballroom air was loaded with heat from dancing bodies. She decided it was time to go. Lady Greenfellow hadn’t stationed herself near the door yet, which meant Alice didn’t need to bid her an official good-bye, though she would have to write a long thank-you letter later. She retrieved her shawl and allowed the manservant to open the massive front doors for her. The cool night air woke her a bit as the servant waved at one of the cabs for hire that waited in the circular drive. It was an old-fashioned one, with four wheels instead of two and a driver who sat up front. In the distance, faint music played—a haunting, compelling melody from a flutelike instrument Alice couldn’t quite identify. To Alice’s surprise, the servant handed the driver a sum of money and told him to take the lady home.

“Courtesy of Mr. Williamson, ma’am,” the servant said, helping her in.

Alice knew she should feel delighted that Norbert Williamson was expressing a continued interest in her, but now that she wasn’t dancing, the champagne was catching up with her and she felt only sleepy. At least Father would be pleased. The cab clattered and rolled through gaslit London streets with Alice dozing in the back. The faint music she had heard earlier grew louder, irritating rather than pleasing. Far off, Big Ben tolled the time with his familiar bells—two a.m.—and the carriage came to an abrupt halt. Alice roused herself and turned to look out the side of the cab.

Facing her was a crowd of plague zombies. The first one reached for the door.

The Doomsday Vault © copyright Steven Harper 2011

I just finished this book, and it’s splendidly awesome. A great deal of fun, with a nicely-realized setting, interesting characters, and a few surprises that really caught me off-guard. Can’t wait for more.

I couldn’t agree more with Michael’s sentiments.

I’ve felt for some time that Steampunk has enormous untapped potential, and this is the first novel I’ve come across that I feel truly makes this emerging genre shine.

While I personally felt the first chapter was the lowest point of the whole book, the novel really takes off at chapter two and just keeps getting better. Both of the main characters are very likable and well-realized, and you really get into their personal motivations and want them to succeed. There are some fantastic twists towards the end of the book that really set up well for the sequel, The Impossible Cube, that’s coming out in May 2012.

Harper’s adventure story has it all–airship battles, Victorian political intrigue, secret police, conspiracy, clockwork automatons of all sorts, mad scientists, amazing Steampunk retro-futuristic gadgets, a surprisingly good romance, and, lest I forget, zombies!